About the Democrat National Convention in Chicago and its History

About the Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the DNC History

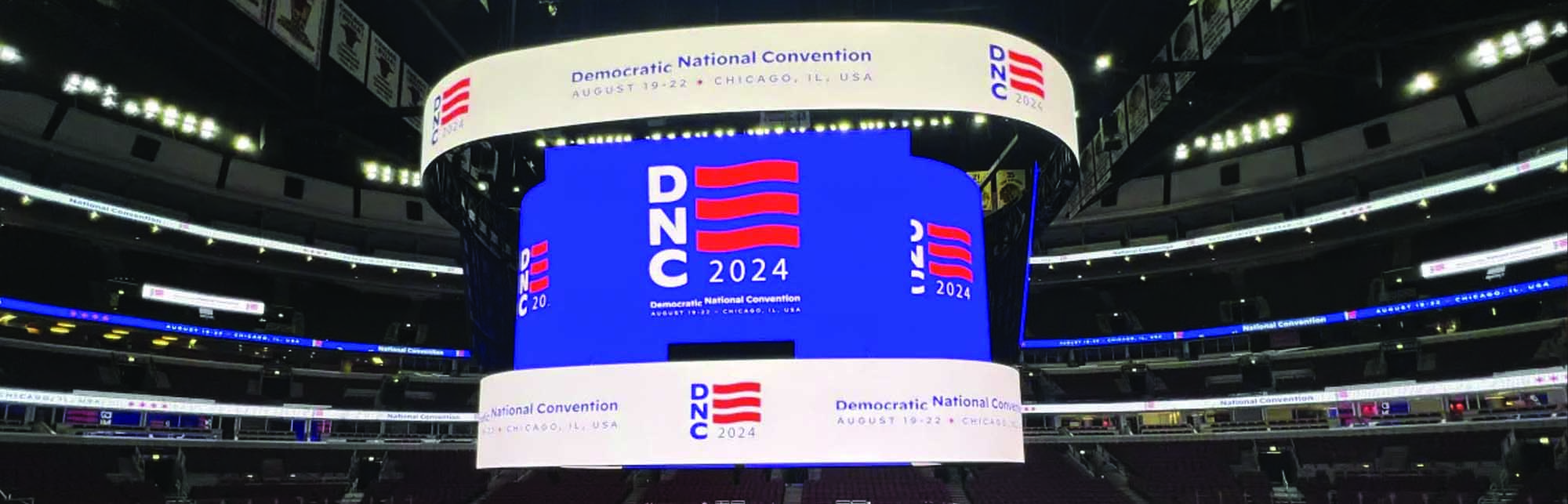

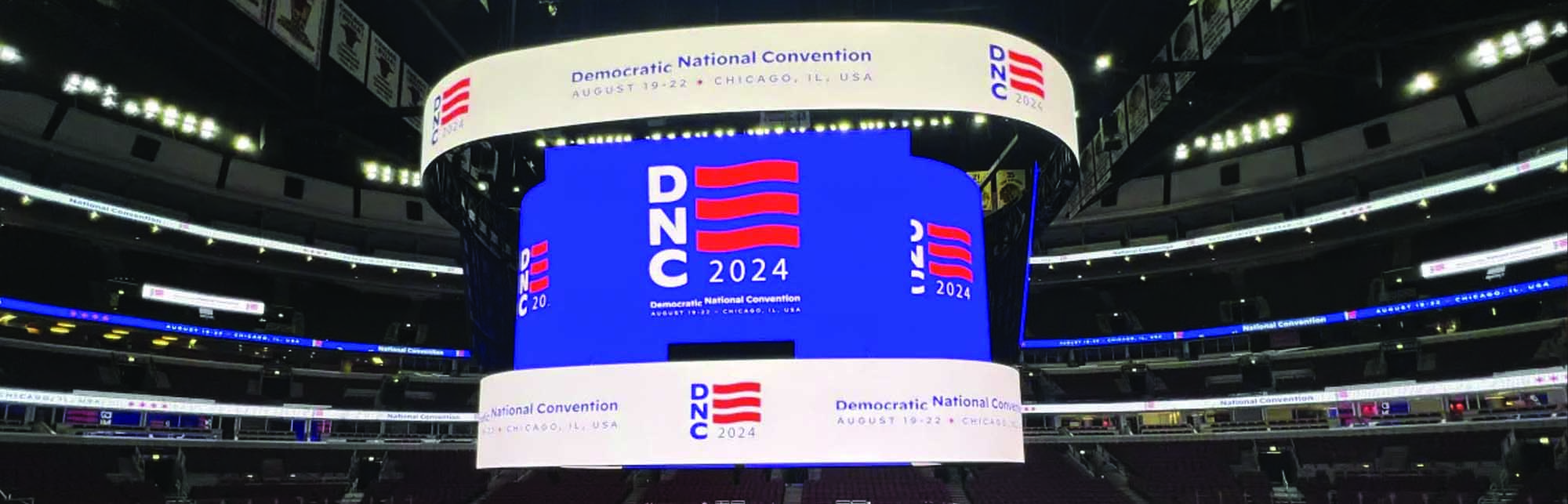

Where is the Democratic National Convention in Chicago 2024?

The Democratic National Convention in Chicago is scheduled for August 19–22, 2024, at the United Center, previously the location of the 1996 Democratic National Convention.

What happens at the Democratic National Convention?

The formal purpose of such a convention is to select the party’s nominee for popular election as President, as well as to adopt a statement of party principles and goals known as the party platform and adopt the rules for the party’s activities, including the presidential nominating process for the next election cycle.

Democratic National Convention History

By 1824, the congressional nominating caucus had fallen into disrepute and collapsed as a method of nominating presidential and vice presidential candidates. A national convention idea had been brought up, but nothing occurred until the next decade: state conventions and state legislatures emerged as the nomination apparatus until they were supplanted by the national convention method of nominating candidates. President Andrew Jackson’s “Kitchen Cabinet” privately carried out the plan for the first Democratic National Convention: the public call for the first national convention emanated from Jackson’s supporters in New Hampshire in 1831.

The first national convention of the Democratic Party began in Baltimore on May 21, 1832, only to nominate a vice presidential candidate as it was clear that Jackson as the party’s natural leader would run for the presidency again. In that year the rule requiring a two-thirds vote to nominate a candidate was created, and Martin Van Buren was nominated for vice president on the first ballot. Although this rule was waived in the 1836 and 1840 conventions – when Van Buren was nominated as presidential candidate by acclamation – in 1844, it was revived by opponents of former President Van Buren, who had the support of a majority (but not two-thirds) of the delegates, in order to prevent him from receiving the nomination after his 1840 defeat. The rule then remained in place until 1936, when the renomination of President Franklin D. Roosevelt by acclamation allowed it finally to be put to rest.

On seven occasions, this rule led to Conventions which dragged on for over a dozen ballots. The most infamous examples of this were in 1860 at Charleston, when the convention deadlocked after 57 ballots: the delegates adjourned, and reconvened in separate Northern and Southern groups six weeks later, and in 1924, where “Wets” and “Drys” deadlocked between the frontrunners, Alfred E. Smith and William G. McAdoo, for 102 ballots over 16 days before finally agreeing on John W. Davis as a compromise candidate on the 103rd ballot. Also, in 1912, Champ Clark received a majority of the votes, but did not subsequently go on to achieve a two-thirds vote and the nomination (Woodrow Wilson won the nomination on the 46th ballot), the only time this happened.

Since 1932, only one convention (in 1952) has required multiple ballots. While the rule was in force, it virtually assured that no candidate without support from the South could be nominated. The elimination of the two-thirds rule made it possible for liberal Northern Democrats to gain greater influence in party affairs, leading to the disenfranchisement of Southern Democrats, and defection of many of the latter to the Republican Party, especially during the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s.

William Jennings Bryan delivered his “Cross of Gold” speech at the 1896 convention, while the most historically notable and tumultuous convention in recent memory was the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Illinois, which was fraught with highly emotional battles between conventioneers and Vietnam War protesters and an outburst by Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley. Other confrontations between various groups, such as the Yippies and members of the Students for a Democratic Society, and the Chicago police in city parks, streets and hotels marred this convention.

Following the 1968 convention, in which many reformers had been disappointed that Vice President Hubert Humphrey, despite not having competed in a single primary, easily won the nomination over Senators Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern (who was announced after the assassination of another candidate, Senator Robert F. Kennedy), a commission headed by Senator McGovern reformed the Democratic Party’s nominating process to increase the power of primaries in choosing delegates in order to increase the democracy of the process. Not entirely coincidentally, McGovern himself won the nomination in 1972. The 1972 convention was significant in that the new rules put into place as a result of the McGovern commission also opened the door for quotas mandating that certain percentages of delegates be women or members of minority groups, and subjects that were previously deemed not fit for political debate, such as abortion and lesbian and gay rights, now occupied the forefront of political discussion.

The nature of Democratic (and Republican) conventions has changed considerably since the 1972 McGovern reforms (which have largely influenced the Republican primaries as well). Every four years, the nominees are essentially selected earlier and earlier in the year, so the conventions now officially ratify the nominees instead of choose them (even the close race of 2008, which was not decided until early June, did not change the modern function of the convention, as superdelegates and Hillary Clinton’s withdrawal ensured Barack Obama’s win before the convention).

The 1980 convention was the last convention for the Democrats that was seriously contested (when Ted Kennedy forced a failed vote to free delegates from their commitment to vote for Jimmy Carter). The 1976 convention was the last where the vice-presidential nominee was announced during the convention, after the presidential nominee was chosen (Carter chose Walter Mondale). The 1996 convention that nominated Bill Clinton was accompanied by protests resulting in the arrest of Civil Rights Movement historian Randy Kryn and 10 others.[8]

Prior to the 2020 convention in Milwaukee (which due to COVID-19 was moved from the larger Fiserv Forum to the smaller Wisconsin Center), the 1984 convention at the Moscone Center in San Francisco was the last Democratic Convention to be held in a convention center complex; all the intervening years saw their conventions held in sports arenas.